Can the WHO and the United Nations impose sanctions on your sovereign country?

Written by Shabnam Palesa Mohamed

Sanctions are a powerful instrument of political control and economic profit. One of the rare but critical topics relevant to the international campaign to #ExitTheWHO is whether the World Health Organisation and the United Nations can impose, influence or recommend specific sanctions. The sanctions could be implemented against countries that choose to not comply or cannot comply with International Health Regulations, the proposed new pandemic treaty, or other legislative attempts that curtail rights, freedom and sovereignty.

The accelerating and profitable globalist march towards unprecedented levels of ‘1984’ style totalitarianism – using censorship, vaccine passports, 15 minute cities, and CBDC’s continues. It is plausible that the WHO and the UN will move to impose, influence or recommend sanctions against countries that do not want to or cannot comply with its centralised health agenda and undemocratic legislative attempts.

At last year’s World Health Assembly 75, the 47 nation African bloc voted surprisingly, against most amendments to the International Health Regulations, stating that they were broad, rushed, and can pose a threat to national sovereignty. Since then, no doubt with persuasive behind the scenes manoeuvres, some of the most disturbing amendments are being proposed by African countries. Many relate to financing for the cost intensive provisions of IHR amendments and the proposed pandemic treaty or accord. Africa cannot afford more debt slavery.

Countries that could be sanction targets for non-compliance with the WHO and the UN, include but are not limited to, those in the steadily growing BRICS initiative: Brazil, Russia, India, China and South Africa. Iran and Malaysia are reported to have expressed reservations to the proposed IHR amendments at last year’s World Health Assembly 75. Russia is making decisive moves in the international arena and could possibly exit the WHO. In addition, India raised serious audit concerns on irregularities with WHO financials, including missing assets.

What authority does the WHO have and what level of control does it want?

The ambit of the overwhelmingly privately funded WHO, contained in its extensive constitution, can be interpreted as overly broad and sweeping, and thus, unknown to non-participants, has always posed a potential threat to individual health and national sovereignty.

The WHO’s constitution states in Chapter 2 – Functions – Article 2: In order to achieve its objective, the functions of the Organization shall be: (v) generally to take all necessary action to attain the objective of the Organization. However Article 21 of the WHO’s constitution is specific about making (non-binding) regulations, limiting the WHO to just five areas.

Proposed amendments to the new pandemic treaty include a dangerous clause that would change the WHO’s role from a UN agency that shares recommendations, to a dictatorship whose elitist and secretive attempts at legislation are binding and mandatory on member states, violating fundamental human rights and freedoms. However, health freedom advocates agree that WHO has no actual authority in the law.

In effect therefore, with both IHR amendments and the proposed new treaty, the WHO is acting ultra vires in its Big Pharma driven power grab, in collusion with naïve or compromised member state delegates. Ultra vires is defined in the law as: acting beyond the scope or in excess of legal power or authority. Ultra vires acts of impunity by the WHO could accelerate a mass defund and exit of the agency.

WHO’s negotiating body on a proposed pandemic treaty

What is the basis for raising the red flag on sanctions?

Health is no longer just health, as it is defined in the WHO’s constitution. Through Covid-19, and other controversially declared pandemics, health is now a multi-billion dollar health security industry. With it, creeps in the tyranny of secrecy, surveillance, vaccine certificates, forced quarantines, and the undemocratic censorship of free speech. Given the absence of public participation, the WHO is a strategic spear for oligarchs and corporations, and given international resistance to its power grab, it become desperate and argue or push for sanctions.

Reported in 2021: “In 2021, German Health Minister Jens Spahn called for sanctions against countries that hide information about future outbreaks. Citing the World Trade Organization’s power to sanction countries for non-compliance, Spahn said “there must be something that follows” if countries fail to live up to commitments under a new pandemic treaty that the World Health Assembly will take up in November.”

Further, it is entirely under reported that controversial “World Health Organization Director-General Tedros Adhanom Ghebreyesus also urged countries to consider the idea as they take up the treaty, a legally binding tool. The treaty should “have all the incentives, or the carrots” to encourage transparency, Tedros said, appearing at a press conference with Spahn in Berlin. “But maybe exploring the sanctions may be important,” he added.”

Also reported in 2021: “Speaking at the WHA in June, Mike Ryan, WHO Health Emergencies Programme Executive Director, also spoke out in favour of the treaty, despite the fact that WHO technical staff have historically avoided taking positions on controversial policy choices before member states. “My personal view is that we need a political treaty that makes the highest-level commitment to the principles of global health security — and then we can get on with building the blocks on this foundation.”

I engaged renowned international law expert Professor Francis Boyle about the possibility of sanctions via the WHO. He had no doubt “They will pursue sanctions against countries that do not comply with their orders, coming from Geneva. Both economic and political sanctions. However, they will only have the power to pursue sanctions if we accept their authority. We cannot. We must exit the WHO.”

Professor Francis Boyle

UN Power Grab. Can it impose or influence sanctions?

With far less public scrutiny currently than the controversial WHO, the United Nations is simultaneously seeking exponential new powers and stronger global governance mechanisms, including multilateralism, to deal with what they define as international emergencies.

UN Secretary-General Antonio Guterres’ Common Agenda report arises from a UN declaration on the commemoration of its seventy-fifth anniversary. This report states “All proposed actions are designed to accelerate the achievement of the Sustainable Development Goals. Our Common Agenda is intended to advance the 12 themes of the declaration.”

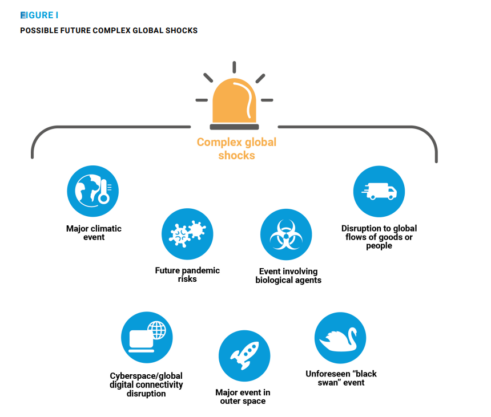

In March 2023, UN secretary-general Antonio Guterres released a related policy brief: To Think and Act for Future Generations – OUR COMMON AGENDA – Policy Brief 2 – Strengthening the International Response to Complex Global Shocks – An Emergency Platform.

One of this policy brief’s 12 key themes is ‘Being Prepared’, which includes:

1. Emergency Platform to be convened in response to complex global crises

2. Strategic Foresight and Global Risk Report by the United Nations every five years

3. On global public health:

a) Global vaccination plan

b) Empowered WHO

c) Stronger global health security and preparedness

d) Accelerate product development and access to health technologies in low- and middle-income countries

e) Universal health coverage and addressing determinants of health

Under the topic of addressing major risks, Guterres states:

98. An effort is warranted to better define and identify the extreme, catastrophic and existential risks that we face. We cannot, however, wait for an agreement on definitions before we act.

99. Learning lessons from the COVID-19 pandemic, we can seize this opportunity to better anticipate and prepare to respond to large-scale global crises. This requires stronger legal frameworks, better tools for managing risks, better data, the identification and anticipation of future risks, and proper financing of prevention and preparedness. Importantly, however, any new preparedness and response measures should be agnostic as to the type of crisis for which they may be needed. We do not know which extreme risk event will come next. It might be another pandemic, a new war, a high-consequence biological attack, a cyberattack on critical infrastructure, a nuclear event, a rapidly moving environmental disaster, or something completely different such as technological or scientific developments gone awry and unconstrained by effective ethical and regulatory frameworks.

101. Secondly, I propose to work with Member States to establish an Emergency Platform to respond to complex global crises. The platform would not be a new permanent or standing body or institution. It would be triggered automatically in crises of sufficient scale and magnitude, regardless of the type or nature of the crisis involved. Once activated, it would bring together leaders from Member States, the United Nations system, key country groupings, international financial institutions, regional bodies, civil society, the private sector, subject-specific industries or research bodies and other experts. The terms of reference would set out the modalities and criteria for the activation of the platform, including the scale and scope of the crisis; funding and financing; the identification of relevant actors who would form part of it; the support that it would be expected to provide; and the criteria for its deactivation. The platform would allow the convening role of the Secretary-General to be maximized in the face of crises with global reach.

DIAGRAM: Policy Brief 2 – Strengthening the International Response to Complex Global Shocks – An Emergency Platform

The emergency platform would be activated during any event that is deemed to have a global impact, and would provide the UN the authority to actively promote and drive an international response. Antonio Guterres, UN secretary-general, declared: “I propose that the General Assembly provide the Secretary-General and the United Nations system with a standing authority to convene and operationalize automatically an Emergency Platform in the event of a future complex global shock of sufficient scale, severity and reach.”

The policy further argues that such authority would “Ensure that all participating actors make commitments that can contribute meaningfully to the response, and that they are held to account for delivery on those commitments.” While the policy states that the emergency authority would have limited duration, it also states that the UN would be able to extend its own powers if it decides to do so. These powers would effectively render public consensus unnecessary, democracies obsolete, and the role of politicians largely irrelevant.

These all encompassing areas of expanded emergency powers relate to:

- pandemics

- wars and nuclear events

- climate or environmental events, degradation or disaster;

- accidental or deliberate release of biological agents;

- disruptions in the flow of goods, people, or finance;

- disruptions in cyberspace or “global digital connectivity;”

- a cyberattack on critical infrastructure

- a major event in “outer space;”

- “unforeseen risks (‘black swan’ events)

- technological or scientific developments gone awry – and unconstrained by effective ethical and regulatory frameworks.

What does the UN have planned?

On September 20th, the UN intends to adopt a high level political declaration on pandemics. In my analysis, the UN pathway to the one health and one world government agenda is a back up plan to the WHO’s trajectory which is increasingly exposed and resisted.

The UN is planning to host its related ‘Summit of the Future’ in September 2024. Guterres stated “The Summit of the Future is an opportunity to agree on multilateral solutions for a better tomorrow, strengthening global governance for both present and future generations.” The UN website states “The General Assembly welcomed the submission of Our Common Agenda and passed a resolution to hold the Summit on 22-23 September 2024, preceded by a ministerial meeting in 2023. An action-oriented Pact for the Future is expected to be agreed by Member States through intergovernmental negotiations on issues they decide to take forward.”

Sanctions are action that is taken or an order that is given to force a country to obey international laws. There are several types of sanctions imposed through the United Nations:

- Economic sanctions – typically a ban on trade, possibly limited to certain sectors such as armaments, or with certain exceptions (such as food and medicine)

- Diplomatic sanctions – the reduction or removal of diplomatic ties, such as embassies.

- Military sanctions – military intervention

- Sport sanctions – preventing one country’s people and teams from competing in international events.

- Sanctions on the environment – since the declaration of the United Nations Conference on the Human Environment, international environmental protection efforts have been increased gradually.

- Economic sanctions are distinguished from trade sanctions, which are applied for purely economic reasons, and typically take the form of tariffs or similar measures.

It is plausible that the UN’s controllers realise that the world is pushing back against the WHO’s overreach, or find it irrelevant to real health. Given that sovereign nations will choose to exit the WHO, the UN decided to launch plan B and ascribe to itself even greater powers. Technically, there is no legislation to exit the United Nations within the UN Charter. Again, this is a critical issue of national sovereignty.

The United Nations Children’s Fund or UNICEF’s 2020 Annual Report highlights USD 717 million in donations from the private sector, which is 21 percent of income overall. Lucrative corporate partnerships include Unilever, Louis Vuitton, and Microsoft, while foundation partners include Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation and Mastercard Foundation. It also prides relationships with the World Economic Forum and the International Chamber of Commerce. National committees fundraise from individual donors and corporations at the national level, to support UNICEF globally. The UN’s programmes therefore are heavily dependant on private funding. Funding crowns influence.

UN secretary general Antonio Guterres with WHO director general Adhanom Tedros Ghebreyesus

Can the WHO and the UN collaborate on sanctions?

The WHO is an agency of the United Nations.

- In 2015, on punishing member states who violate the IHR, as reported: “United Nations health officials said they want to impose sanctions on countries that do not comply with public health regulations meant to avoid the spread of dangerous epidemics, such as the Ebola outbreak that killed more than 9,000 people and ravaged domestic health care systems in West Africa last year. World Health Organization Director Margaret Chan said she is investigating ways to reprimand countries that disobey the International Health Regulations (IHR) — a set of rules adopted in 2005 and mandate that countries set up epidemiological surveillance systems, fund local health care infrastructure and restrict international trade and travel to affected regions deemed unsafe to the public, among other provisions. Chan is on a panel set up by U.N. Secretary General Ban Ki-moon, who instructed the group to think of ways to hold countries accountable for how they manage public health crises and punish those who violate the IHR.”

- In 2022, according to commentators in a policy article: “In order to enforce compliance, some commentators have recommended concluding the treaty at the United Nations level. However, we fear that it has been already decided with the INB (mandated by WHASS) that a treaty will be developed under the roof of WHO. They added: “To move on with the treaty, WHO therefore needs to be empowered — financially, and politically. If international pandemic response is enhanced, compliance is enhanced. In case of a declared health emergency, resources need to flow to countries in which the emergency is occurring, triggering response elements such as financing and technical support. These are especially relevant for LMICs, and could be used to encourage and enhance the timely sharing of information by states, reassuring them that they will not be subject to arbitrary trade and travel sanctions for reporting, but instead be provided with the necessary financial and technical resources they require to effectively respond to the outbreak. High-income settings may not be motivated by financial resources in the same way as their low-income counterparts. An adaptable incentive regime is therefore needed, with sanctions such as public reprimands, economic sanctions, or denial of benefits.”

* Tweet CHD Africa if you agree that sanctions are possible and must be opposed internationally. Use the #StopSanctions

United Nations headquarters in Geneva, Switzerland

Sanctions are a blunt and inhumane weapon that cause devastating harm

In 2000, Kofi Annan, former Secretary General of the UN said: “However, just as we recognize the importance of sanctions as a way of compelling compliance with the will of the international community, we also recognize that sanctions remain a blunt instrument, which hurt large numbers of people who are not their primary targets. Further, sanctions need refining if they are to be seen as more than a fig leaf in the future. Hence, the recent emphasis on targeted sanctions which prevent the travel, or freeze the foreign bank accounts, of individuals or classes of individuals – the so-called ‘smart sanctions’.”

Do sanctions work? “UN targeted sanctions, which are packages of sanctions imposed by the UN Security Council, have been successful in leading to intended policy change only 10% of the times, and limited the policies they intended to change in 28% of cases, but led to a reduced life expectancy in the targeted countries by 1.2–1.4 years. Economic sanctions have also been criticised for the potential collateral damage to third states they can cause. For this reason, some authors suggest that economic sanctions should be banned, as they are having detrimental effects on health and nutrition of civilians.

Countries themselves can and do impose dangerous sanctions. A 2022 UN security council meeting on sanctions recorded: “Unilateral sanctions, which are sanctions imposed by (groups of) states and not by the UN Security Council, are particularly controversial. Unilateral sanctions have also been criticised for being disproportionately imposed on low-income and middle-income countries by wealthier countries, for example, by the Kenyan representative in a Security Council debate on sanctions on 7 February 2022: ‘The frequency and reach of unilateral sanctions have led to a growing view that they are the weapons of the strong against the vulnerable or weak’.”

International human rights law vs sanctions and health impact

- The Universal Declaration of Human Rights, in its first article, states that ‘all human beings are |…| equal in dignity and rights’, which includes the right to health. Article 25 specifies that ‘everyone has the right to |…| health and well-being |…| including medical care’.

- In the UN Convention on the Rights of the Child, article 24 states that ‘state parties recognize the right of the child to |…| the highest attainable standard of health and to facilities for the treatment of illness and rehabilitation of health. State parties shall strive to ensure that no child is deprived of his or her right of access to such health care services’.

- General Comment No.14 of the UN Committee on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights (CESCR) on the right to the highest attainable standard of health, the right to health is a fundamental human right which is necessary for all other human rights to exist and be exercised.

- “The use of sanctions designed to hurt a country’s healthcare sector is clearly incompatible with respecting citizens’ right to health. Accordingly, the general comment No. 14 of the CESCR calls on states to refrain ‘at all times’ from sanctions on medicines and medical equipment. However, sanctions on other healthcare products and, in fact, other non-healthcare products may as well interfere with the right to health, and, thus, need to be subject to scrutiny.”

- The Impact of Sanctions. Case Study: Iraq

WHO’s World Health Assembly 75

WHO’s World Health Assembly 75

Freedom faces an existential threat via the WHO and the United Nations

South African Precious Matsoso, co-chair of the International Negotiating Body (INB), formed to negotiate the terms of the proposed pandemic treaty or accord, admitted openly that punitive measures have not been shown to work “anywhere” in the world. However, she said, there must be accountability measures while recognizing countries’ sovereignty. “We have to recognize that they’re sovereign, and they keep on reminding us that they are sovereign states.” It is positive to note that more states do recognise the real threat to sovereignty.

Not all states are considered equal. Smaller countries are at a distinct disadvantage in participating, negotiating and making decisions at the hierarchical WHO. Significantly, Matsoso was transparent about failures in equal participation. “A number of smaller delegations have always expressed concerns about organizations of multiple meetings, where they have to travel from afar, and not even having the capacity to participate in the negotiations,” Matsoso said. “And they have repeatedly requested that you must avoid parallel sessions.” To little avail.

Given the rapidly growing distrust in the WHO, its historical failures and harms, Covid-19 failures and harms, and the fact that it cannot maintain independence because it is a largely privately funded entity; it is plausible that the WHO and/or the UN will move to impose or influence sanctions via the World Trade Organisation, ahead of Agenda 2030. This act of aggression weaponises the WHO and/or the UN against countries that influential funders and unethical stakeholders have an interest in destabilising for power and resource control.

This sinister strategy has disturbing implications for democracy, peace, and prosperity around the world. Freedom faces an existential risk through unelected bureaucratic entities. Nations can and must protect their sovereignty by defunding and exiting WHO, and, by critically assessing the true nature, value, and risks of continued membership in the 78 year old United Nations. Not to do so, means to ignore the risks of UN peacekeepers, known to commit crimes with impunity, being deployed in your country to enforce UN and WHO governance.

Take Action with CHD Africa in 5 steps:

- Share this article. If you can, translate and email to [email protected]

- Raise awareness amongst your country’s people, activists, politicians and media

- Sign up to CHD Africa’s newsletter for informative content, campaigns and resources

- Follow CHD Africa on 6 social platforms for news, action alerts, and updates

– Telegram: t.me/CHDafrica

– Twitter: https://twitter.com/CHD_Africa

– Instagram: https://www.instagram.com/af.childrenshealthdefense/

– Facebook: https://www.facebook.com/CHDafricachapter

– Rumble: https://rumble.com/user/ChildrensHealthDefenseAfrica

– Tiktok: https://www.tiktok.com/@chdafrica?is_from_webapp=1… - Help CHD Africa do more by donating to support our dedicated work

- Volunteer to help CHD Africa reach more of Africa and the world

Shabnam Palesa Mohamed is executive director and chapter coordinator for Children’s Health Defense Africa. She is an activist, journalist, lawyer and mediator, with over 20 years of experience in human rights work. To share information relevant to this article, Twitter: @ShabnamPalesaMo

Shabnam Palesa Mohamed is executive director and chapter coordinator for Children’s Health Defense Africa. She is an activist, journalist, lawyer and mediator, with over 20 years of experience in human rights work. To share information relevant to this article, Twitter: @ShabnamPalesaMo